Alberg 30 Offshore Shakedown

A Teaching Passage Down the East Coast

We arrived at the boat in Branford, CT at midnight, road-weary from a 17 hour drive up from Brunswick, GA. My sole companion, Sergei, a Moscow real estate broker, beams with pride and adoration as he surveys his boat under the dock lights at Dutch Wharf Marina. A couple months earlier I had helped Sergei arrange the purchase of this classic 1972 Alberg 30 sloop #499, named Bells, from the previous owner who had commissioned me to refit the boat four years earlier. Because that previous owner was working to a monthly budget and he kept adding more jobs and upgrades to the list as they came to mind, it became a part-time two-year project to completely dismantle, repair and modify, paint inside and out and prep for sea.

I call this the Voyager Edition Alberg 30 based on the thorough refit using ideas learned from earlier boat projects and the two circumnavigations on my Pearson Triton, Atom. The Voyager title puts a name to all the repairs and modifications I feel the original boat can be improved with. Her deficiencies were addressed and key improvements made, such as replacing the troublesome old inboard gas engine with a 6 HP outboard in a tilt-up outboard well in the lazarrette locker, integral water tanks, watertight bulkheads in critical areas, new hatches and portlights, sails, rigging, chain plates enlarged and knees reinforced, self-steering windvane, solar panels, new electrical and plumbing systems, all new exterior teak, and a hundred other details big and small.

I found myself back aboard Bells with her current owner who is new to offshore sailing, having been to sailing school and completed a shared two week sailboat charter vacation in Croatia a few years back, but lacking real offshore sailing experience. He hired me to assist him sailing the boat back to Brunswick and along the way teach him as much of the full range of sailing skills as the time allowed. My other task was to help him improve his conversational English. Although he reads the language well, he has had few chances to practice speaking it, which is a whole different challenge.

Beyond testing out my design modifications on an actual voyage, my brief return to the sea from a harried, too busy life ashore these past several years is something I sorely needed. I’m sure it would have been the very thing my doctor ordered, if I had troubled to ask him, since he is a sailor too and may even share a bit of the same affliction, or at least, understand the cure. To add to the current stress of obligations to work on several clients boats and still find some time to sail Atom, I now needed to quickly prepare everything required for this passage. Sergei had his flight booked for September 8. I needed to be ready to go within a couple days.

We also were dealing with tropical storm Hermine that passed near Brunswick after crossing over Florida from the Gulf a few days before departure. The result at our inadequately protected docks in Brunswick that faced a four mile open fetch to the south, was four boats sunk and many others damaged as the too small and lightly built floating breakwater was overwhelmed and the docks began to break up. The day before the storm arrived I was still optimistic that it would be so weakened by land as all previous storms had been that hit this area in the past few decades, that I did not move my boat to a better protected spot. I put out extra mooring lines on my absent friend’s boats and lashed down dinghies and removed sails. I stupidly shared my confidence with a neighboring boat owner and said “I’m not too worried because all these weaker hurricanes that cross over from the Gulf lose much of their strength before they get here.” That was generally true. But this storm, it turned out, had a large, healthy wind-field and tracked exactly the wrong way so that the strongest wind sector of sustained 40 knot southerlies gusting to 60 passed directly over us. Thankfully, his boat survived with only minor damage.

In Brunswick, Sergei rented the largest Ford sedan available for the one-way trip to Branford. We carried so much gear with us that the car was filled to the roof. I borrowed items from Atom that might prove useful such as the storm drogue, extra gas and water cans, storm trysail, spare anchor and rode, charts, spare GPS, Satellite communicater, SSB receiver, mozzie screens, and bags and bags of other equipment and provisions.

Along the way, time and again we had trouble using his Russian bank credit card at the gas pumps. Sergei would have to go inside and give his card to the attendant, who inevitably asked for his zip code. The card didn’t use a zip code but some other identification number that the American machines had trouble deciphering. Sometimes it worked, more often not.

“What’s your zip code?” the young lady with a southern drawl asked him.

“What?” Sergei said.

They both repeated their same questions in a verbal stand-off.

“Are you from Canada?” the woman finally asked, as if that explains white people with foreign accents using non-functioning credit cards in her shop. As she repeated “Canada?” and Sergei kept replying “What?” a long line of customers built up behind him. I interrupted and said “Yes, he’s from Canada and the zip code is a different type.” Somehow that soothed the woman. She punched a few more keys and the card was accepted. It was a similar scene all up the east coast. I kept telling everyone he’s from Canada since I thought they might not want to deal with a Russian credit card. Once we got closer to Canada in New England, it backfired when the man holding Sergei’s card said “He don’t sound like he’s from Canada and whaddaya mean they have no zip code in Canada?” I kept my mouth shut after that. Finally, in a Branford hardware store where we went to buy a $6 thread tap, his bank decided it was a good time to cancel the card. Getting to sea was going to be a huge relief.

Sergei soaks the toilet compost as we load the Alberg 30 Bells with supplies.

We piled our gear haphazardly into the boat that first night and sunk into our bunks. One minute after Sergei’s head hit the pillow his throat emitted a deep rattling, rasping noise as I’ve heard nowhere else in nature. My bunk was two-feet away from his in the main salon. He roared so loudly I felt the vibrations run right through me. Oh Christ, I thought, with my slight insomnia even in quiet surroundings, how the hell am I going to get any sleep on this trip? My wife, Mei, had warned me she heard him snore loudly the night before at our house in the guest room thirty feet away through two closed doors. At least on the passage, we would sleep in shifts and he could snore all he wanted while I stood watch. Then I could sleep while he silently stood his watch. Aside from this one minor fault beyond his control, Sergei proved to be the most pleasant, helpful, and intelligent companion you could hope to share a small boat with. And Mei says I too snore sometimes, but thankfully not at Sergei decibels.

The next morning we rose early, Sergei refreshed and fit; myself red-eyed and foggy-brained from the eardrum assault. I splashed cold water on my face and stood up to face a busy day.

“How was your sleep, James?” Sergei inquired with his soft Buddha-like smile.

“Not too bad,” I lied. I looked forward to better sleep once underway when Sergei was standing watch.

Although the previous owner had sailed the boat locally for two years, there were still many last minute jobs to do. I began by handing Sergei an extra-large wetsuit I had bought for him, my mask, snorkel, fins and scrub brush, and said, “You can begin by cleaning the bottom,” and made a scrubbing motion with my hand while pointing at the water. We pulled and pushed his 5’9″, 240 pound bulk into the snug-fitting suit. “I plan to lose weight on the trip,” he said prophetically.

He had already sampled the local waters soon after we awoke that morning. I was eating a bowl of muesli when I heard a call from outside the boat, “James, Help!” I found Sergei clinging naked to the dock above his head. It took some time for me to locate our rope swim ladder because we hadn’t unpacked yet. Eventually I hung it over the side and he climbed out and put on his shorts. Were early morning naked swims in dirty rivers a traditional Russian activity, I wondered? The river beckoned him in but the dock was a bit too high to climb out. I later discovered that 48-year-old Sergei is a physically and psychologically tough individual who has backpacked in Tunguska and other remote parts of Siberia for months at a time. Although built strong as a Cape buffalo, he has the gentle, easy to laugh, unperturbable temperament of the Dalai Lama.

Dutch Wharf occupied a section of a winding narrow river near the old town of Branford, itself restored and looking neat and orderly and stuck in time like the New England town in the movie Groundhog Day. Our neighbor boats at the marina comprised all sorts of classic craft, from a pristine varnished teak Hans Christian 43 to Alberg-designed “classic plastics” to restored wooden sailboats. Gleaming varnish and polished bronze were all around us. The yard took such pride in their work that even all the dock handrails were kept brightly varnished.

The remainder of the day and late into the night was a flurry of stowing and inventorying gear, shopping, checking every piece of equipment, and making all secure for sea. One of the first things I noticed when test hoisting the mainsail and installing new reef lines was that the sail track was separating from the mast 25 feet above the deck. This was potentially a big problem that would prevent our departure until fixed. I had supplied that Tides Marine sail track with the boat but had not had time to check the fit before the boat was trucked from Georgia to the owner’s place in Connecticut. The manufacturer had made the clearances a couple millimeters too wide and it had just barely stayed in place these past two years. But now it was coming off and I had mostly myself to blame for not checking it more carefully. I spent several hours hanging from a bosun’s chair drilling and tapping machine screws every 16-inches the entire length of the track to fix it solidly in place. Fortunately, I was prepared to work on the boat and had brought along a drill, angle grinder, spare inverter, and full tool bag. Boat maintenance is never truly finished. It either goes on continuously or is neglected for a time and then you’re back to it again.

We also dealt with assorted jobs such as a sticking sliding hatch, sewing additional attachment lines to the bunk lee cloths, securing the deck chain pipe whose hook was missing, and priming the composting toilet with dried coconut choir that we first softened in water. I planned to not contribute to the compost contraption by instead using the “bucket and chuck it” method, but it was now ready for the owner to use. All other jobs dealt with, the next morning we motored Bells down the river into Long Island Sound to begin the 850 mile passage to Brunswick.

Before we could turn south, the barrier of Long Island forced us to sail 50 miles east to exit the sound. Numerous attractive anchorages and rivers flow into the sound from the Connecticut shore and many more anchorages are available among the islands at the eastern end of the sound. Having made a late start that day, after 20 miles we stopped for the night at Duck Island Roads. Here I showed Sergei how to make the approach and anchor under sail only. It was a quiet little spot formed by two long breakwaters extending either side of a tiny island a half-mile offshore. Here we waited until daylight and a fair tide to navigate the tricky Plum Island Gut. At sunrise, we again left the motor in its tilted up resting position as Sergei hand-cranked in the 33 lb Rocna anchor with the Lofrans windlass. Once up, we hoisted sail for a silent exit. Using the Eldridge tide table book onboard, we timed our transit of the narrow cut during the late morning ebb tide. We rocketed through the cut at a combined sailing and current speed of 9 knots. Although today it was fairly tame, currents here reach 5 knots or more with swirling eddies and dancing overfalls in wind against tide conditions that can be unmanageable for slow, small sailboats.

Running with reefed sails.

By late afternoon we rounded Montauk Point to enter the open Atlantic. On our heels was a cold front marked by an ominous line of dark clouds approaching fast from the northwest. I planned to use this frontal passage to provide us fair following winds during the next few days. First we had to beat into 15-20 knot winds for a few hours until the front shifted the winds to 25 out of the northeast. The sea was kicking up. Sergei swallowed hard and said, “I’m feeling… (thumbs through Russian?English dictionary)… nauseous.” I gave him a double dose of seasick pills with some crackers and suggested he rest in his bunk for a few hours. During the next couple days he completely gained his sea legs. Even on that dirty night of wind and rain he cheerfully stood his midnight to 06:00 watch. The next day, the winds had dropped to an easy 15 knots as we flew along downwind still controlled perfectly by the Norvane self-steering windvane. Later Sergei stated with newfound reverence, “I don’t know what we do without Norvane self-steering. It is very needed.” He recognized that expecting the delicate electric tillerpilot to handle a heavy sea and shifting winds was asking too much.

Fifty miles off New York Harbor we passed through fishing grounds where six trawlers were in sight at once as they zig-zagged around dragging nets. One bold skipper turned purposely in front of us and stopped to retrieve his nets. We gybed to alter course and kept a close eye on the rest of the erratic fleet.

Over the next few days as I taught Sergei everything I could think of related to keeping him and the boat safe and moving in the right direction, I was reminded that it is no easy task for beginners to learn in one trip the myriad skills and habits gained from decades of offshore sailing. I felt we did, at least, take a few years off the learning curve. All of these skills were deeply imprinted on me so that I hardly thought about them. Sergei needed to learn how to move low and slow from one hand-hold to the next as we reefed and unreefed the main and furling genoa to the changing winds, set the preventer and whisker pole, managed course changes, set the AIS ship proximity alarm, cooked our meals, plotted and updated our course on the paper charts as well as the GPS plotter, and all the other common tasks involved in navigating a boat at sea.

We lacked a boom vang that had somehow never gotten installed so we rigged up a temporary version with rope tackle. I was thankful we carried new, reeefable sails. On two occasions we used even the third reef in the mainsail since the Alberg 30 and boats like her heel easily and need little sail area to reach hull speed in a moderate breeze. Like my Triton, they don’t at all like to be overpowered.

I have always loved riding upon the heave and roll of the open sea. Or I should say I love it on light air days or days like these going downwind in a fresh breeze. Bashing against a gale or even half a gale is called “beating” for good reason, as it strains both crew and boat. I go to great lengths to avoid beating offshore and will gladly sail an extra hundred miles downwind if I can avoid 10 miles of heavy beating. With wind comfortably aft the beam, the boat gently rolling downwind, we fell into the trance that takes hold – an unreasonable expectation it could go on like this forever.

My mental comfort on this passage was ensured by the knowledge that I had rebuilt or inspected every square inch of this boat. Even so, it took two full days and nights at sea before I could unwind my distracted mind enough to fully appreciate the gifts of the moment. I delighted in catching the top edge of a salmon-colored full moon creeping over the horizon as I handed Sergei a bowl of vegetables and noodles cooked in a single pot and spiced heavily with peppers. In the cockpit we both savored the moonrise and looked forward to its light and companionship through the long night watches. A seagull hovered 10 feet over the cockpit looking down at us then banked back to check the green squid fishing lure trailing from the boat.

“In Greek,” Sergei said, “Larisa means seagull. It is my wife’s name too.” I told him how my boat’s name Atom is from the Greek meaning “small and unbreakable”. We discussed his selection of a new name for his boat and he asked for ideas. Sailors often choose names for their boats that elicit some mood or quality they admire. Legendary names of Wanderer, Islander, Spray, Trekka, Gypsy Moth, and a dozen others rolled off my lips. Sailors also name their boats after their wife, a gesture that should ensure happy days, though having to explain to your new girlfriend that your boat Margaret was named after your ex-wife probably doesn’t help. Sergei soon selected his wife’s nickname of Lora, a dimunitive form of Larisa.

Another sunrise and we glide along at 4.5 knots in a fading wind. She foots along so steady I hesitate to burden her or myself just yet with more sail. Later that morning, as the sea calmed down from its agitated state, the boat felt like a train car barely moving on tracks. I was deceived into thinking the wind had dropped further. In my bunk I looked up from my book surprised to see the GPS speed indicating 6.2 knots. Yes, this old girl sails surprisingly well when set up properly.

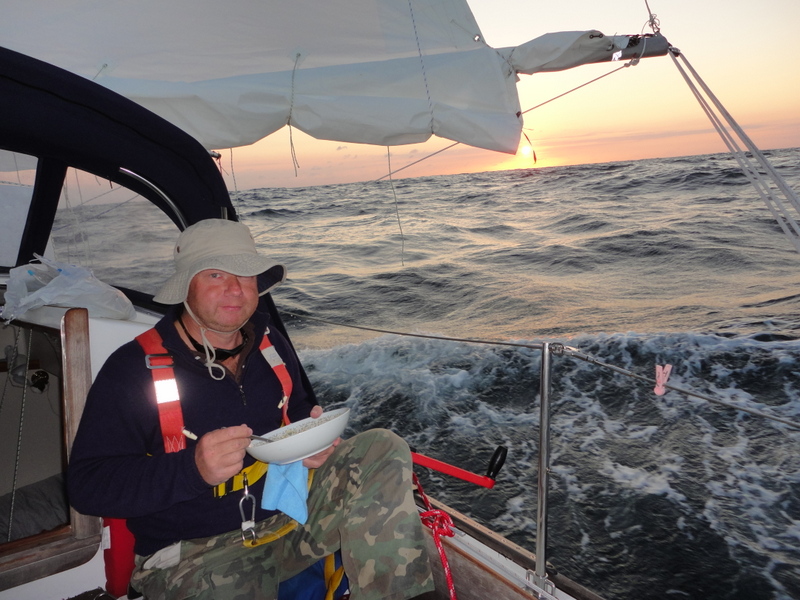

Dinner at sea.

An abbreviated satellite text message from my wife comes in: “Everything is fine here. I follow your map position every day.” Fells like precious news. The very possibility of it seems extraordinary since the days of austere and self-indulgent lonely solo passages of my youth. For years I sailed without any communications equipment beyond a postcard ready to drop at the next island. Incoming mail was addressed to me at an ever-changing string of Post Offices using “Poste Restante.” Nowadays we can select from reasonably affordable electronics such as GPS plotters, AIS, SSB, vastly more efficient radar, satellite communications, charting software on tablets, and all the rest. I’ve had several of these aboard Atom at one time or another as I explore the range of possibilities and test items out for my clients needs. On this trip we have no SSB, but communicate with home base and even download weather forecasts when beyond reach of VHF shore stations, with a handheld Delorme InReach SE satellite messaging device picked up on amazon for $264. Using this device, people can follow your journey through automated position reports on a webpage. It also has an SOS emergency feature that comforts those back home. We selected the service plan that allows 40 messages per month for $35. Go over your limit and they cost 50 cents each. Seems to be a worthwhile device to carry if you need to communicate with anyone.

We sailed Bells (now Lora) into Norfolk, VA early one morning after just three days at sea. Sailing conservatively with reefed sails whenever it felt more comfortable, our average was 120 miles per day and 130 in the past 24 hours. We diverted course to avoid persistent headwinds and a post-tropical storm lingering off the Carolinas south of Cape Hatteras. We could have gone in to Virginia Beach and sat there waiting maybe five days for a weather window. Instead, we decided to follow the Intracoastal Waterway (“The Ditch”) for 200 miles down to Beaufort, NC and resume the passage offshore from there. I felt a touch of the same stirring emotions re-entering society at Norfolk as I had after an isolated pilgrimage of 43 days at sea in the Pacific. Passagemaking under sail never gets old.

Through the busy naval port at Hampton Roads we sailed passed aircraft carriers and lesser ships being repaired or prepped for sea duty. Sergei was wide-eyed and camera ready. Twelve miles upriver we entered the only lock on this stretch of the ICW at the town of Great Bridge. When I last travelled these waters 33 years ago, the town was a speck on the map. Today it has grown into the typical suburban sprawl of strip malls and housing developments that extends miles outside any big town or city such as nearby Norfolk. A cranky old coot on the lock wall above us, shouted at Sergei, “Put the middle of the line on my hook.”

Sergei, not understanding, tried to give the man first one end of the line and then the other.

“The middle, I said, the middle!” They went back and forth saying “Middle!”, “What?” with the old fellow’s blood pressure and voice rising and his pole stabbing at Sergei, until I went to the bow and sorted it out.

The lock doors shut and the brown waters lifted us one foot to the level of the river ahead. Once through the lock we tied to a cement quay at a riverside park squeezed between the lock and a low bridge where free overnight dockage was provided. I checked the ActiveCaptain website to see what other sailors had reported on their visits to this area and learned there was a good, cheap Mexican restaurant nearby. We walked five minutes to the El Toro Loco and wolfed down huge combo platters for the bargain price of $6.50 each. Our bellies seemed to believe the heavy food was a welcome change from my simple, light, one-pot dinners.

Back aboard, Sergei took to his bunk for that blissful post-passage deep sleep every sailor needs. Again, it soon sounded as if a misfiring Harley-Davidson was revving the throttle inside the cabin. Eventually, I got some sleep regardless.

Our plan for the ICW was to depart each morning at first sign of twilight and motor or sail, as the winds allowed, for the thirteen hours of daylight until sunset. I was on a delivery and had other job commitments at home, otherwise we would have taken our time to do more sailing and sightseeing and less motoring. Travelling the ICW in this region at night is risky unless you know the waterways intimately. For one thing, you need good visibility because occasionally the GPS plotter does not agree with the navigational markers. The tugboat captains do know these waters and often pull and push their unwieldy barges at night. One tug and tow surprised me early that night. I watched through the cabin windows as he passed uncomfortably close, towing a massive bundle of water pipes hundreds of feet long.

At dawn we called the Great Bridge operator on the radio who told us the next opening was at 7 o’clock. We motored into position as the road traffic stopped and the unusual counterbalanced bascule bridge spans parted, lifting up with hydraulic rams that allowed the spans to pivot on massive gear teeth. The lifting was made easy by its enormous overhead counterbalancing concrete weights hanging above each end that road traffic normally passed under.

Motoring Lora along a canal in North Carolina backwaters.

We motored along with ¾ throttle at 5 knots through the still, brackish, tan-bark waters of the canals and rivers from Virginia into North Carolina. The electric autopilot arm gripped the tiller as we occasionally inputted one or two degree course adjustments in the straight canal cuts. Cypress and other hardy trees stood with their trunks underwater along the swampy edge of the canals. We opened three more bridges that day, then the river widened to 3 miles at Currituck Sound, yet held only 5-6-foot depths throughout. We carried on in the calm air dragging a plastic squid lure off the starboard quarter because a young fisherman at Great Lock said it might work for bass. To port we dragged a silver spoon in case he was wrong. We were both wrong and caught nothing during our four days on the ICW.

We anchored that night off Buck Island, itself less than one square mile of bush-covered swampy ground. It felt like the middle of nowhere with no signs of habitation anywhere, except for a cell phone tower. Wilderness tamed by 5 bars of 4G! Sergei swam in the fresh water here as I cooked up a peppery dish of rice and beans. As soon as darkness settled on us a swarm of unidentified flying insects arrived. We ducked inside and set up the hatch screens behind us as they droned audibly. In the morning the deck was completely covered in their now lifeless bodies.

Sergei cranked on the anchor windlass handle as I rinsed the mud from the incoming chain with buckets of river water. We hoisted sail with a fair wind and covered 15 miles at six knots. When we entered the 4-mile wide, 22-mile long Alligator River, the wind increased and shifted on the nose. We double reefed the main, sheeted it in tight, and motorsailed at full throttle doing short zig-zags some 20 degrees either side of the wind to keep the mainsail driving and our speed above 4 knots. This worked well, despite having to negotiate a narrow opening bridge in mid-river. Beyond the bridge the wind increased to 20 knots and the shallow waters kicked up a steep chop. We pressed on with the bow hitting hard into the waves, flinging back sheets of spray. We nearly sailed over a 60-foot-long tree floating down the river that had been uprooted from the shoreline. After that, one of us always kept a close watch ahead for floating hazards. We covered 70 statute miles that day and anchored at Pungo River in a heavy rain.

Underway again the next morning, we caught an unexpected fair wind from the northwest. The VHF marine forecast for this area pronounced southeast winds all day. We had opposite winds because post-tropical storm Julia that had threatened our passage around Hatteras had now moved inland and its center was wandering around directly on top of us. The rain dogged us all day and most of the following day. Motorsailing again, we crossed the very rough Pamlico River. The next night’s anchorage was thick with mosquitoes that pursued us the next morning three miles out into the open sound.

We had moved from the great naval shipyards of Norfolk, through the swamps and canals where vigilant herons stood marsh-side guard on long spindly legs, to the wide tumbling waters of the Albemarle and Pamlico Sounds that reached across twenty miles or more to the wind-swept ocean barrier islands around Cape Hatteras. These four days we sometimes crawled into stiff headwinds, motored in calms, or careened along through canals, rivers, and lake-like sounds under silent sail, pencil marks ticking off on the chart the countless buoys and marker pilings. The pilings were often adorned with mop-top birds’ nests. Over and again we bounced and bashed our way into the steep chop in the wide rivers and sounds and then felt the blessed respite of following the river as it turned downwind where we could ease the sheets and reduce the heeling. If we weren’t on a schedule, we could have enjoyed gunkholing around here for weeks. But there were times here when our slow progress seemed to indicate that my planned 9-10 day delivery trip would have no end in sight. I began to wonder if my dog would remember me or my wife speak to me when I finally returned home.

“Can we drop sail now?” Sergei asked each time we approached a narrow river entrance or canal with a fresh breeze in our sails. Naturally, for a cautious beginner, he feared the sails and trusted the motor. But a sailor needs to believe the opposite and I made some effort to break him of this particular foible. Must be a bad habit universally taught in sailing school. “When in doubt, motor your way out.” But motoring, particularly offshore, except when becalmed is seldom a good plan. Motoring into the wind to reef sails, for example, is dangerous and unnecessary – you’ll likely foul a sheet in your prop one day. Then you have the dilemma of no motor and limited sailing skills.

“Don’t fear the sails”, I said, “they must be used whenever possible.” I tried to drill the message in with a metaphor about the cowboy and his horse – he never doubts or fears his control over the animal. But Sergei’s English wasn’t up to my schooling. Even so, feeling on a roll, I went on with unsolicited advice. “After this trip you will be the captain of your boat. Never show your crew your doubts or indecision. They will read you like a needy, attentive dog reads his master’s moods. Your crew will react and amplify your own faults and insecurities. A happy boat requires a crew with confidence in their skipper. If necessary, fake it until you earn their respect honestly.”

“What?” Sergei replied to the flurry of needless words.

Each day underway, whether offshore or on the rivers, we discussed and tested out every issue regarding the boat and our handling of it in great detail: navigation, reefing, windvane adjustments and sail balance, electric tillerpilot limitations, sheet track positions and angles, preventer and vang, when to use the engine (and when not to), anchor scope and snubbers, pulling into a fuel dock, and all the rest.

Past the sailor’s community of Oriental, NC, on the final few miles to Beaufort, the land became slightly higher and less swampy. Million dollar waterfront homes lined the canal. I noted the changes to the ICW since 1981, when at 23, with my two hometown buddies as crew, I first fled south aboard Atom from the boring, freezing winters of Detroit. Besides the ever expanding home-building and new marinas, many of the low bridges have been replaced by high fixed bridges. For the others, now we call bridge operators on the VHF. Back then I sailed up close and gave a couple mighty trumpet blasts from my conch shell horn. The makeshift horn wasn’t all that loud against the wind and sometimes I needed to land my crew to climb up the ladder to rap on the bridge tender’s window. One time we found him asleep in front of a blaring portable radio.

We caught the ebb tide to carry us past the cruising sailboat crossroads port of Beaufort harbor and out the busy inlet into a calm, sunny sea. The VHF forecast was for light variables and calms the next two days. We could have stayed in Beaufort to await more wind but I knew this boat sailed well in light airs. We motorsailed several hours until cat’s paws scratched across the oily waters signaled a new wind on the beam. Off with the motor, unfurl the genoa, set the windvane. At sunset, we each in turn had a shower in the cockpit footwell with a garden sprayer connected to a modified shower nozzle. I served up two cans of clam chowder with an added chopped onion. We watched Venus brighten low on the horizon. She was an old friend who I knew from my days using celestial navigation, always appears within 47 degrees of the sun in morning or evening twilight. Big dark blotches of cumulonimbus hung in a line across the Gulf Stream waters.

For most of my 6pm to midnight watch I sat on the coach roof leaning against the mast as the boat glided along in the 5 knot SSE wind. Above, the shimmering stars of the Milky Way laid a trail of light to the horizon off the bow. I think of Mei at home, and how she calls it by the Chinese name “Silver River.” Behind us the Big Dipper corkscrews through the hours until it sits level with its pointer stars aligned with Polaris, as always matching our latitude, now at 34 degrees above the horizon. Through the headphones of my MP3 player I absorb the soothing lyrics of Cold Play: “I wanna fly, never come down.”

Sergei appears on deck for his midnight watch, headlamp at the ready and safety harness on. On day one he accepted my requirement for attaching his harness at all times when on deck offshore. Before heading for my bunk I point out our course, the barely perceived true wind direction deduced from our speed and the apparent wind. We both look up at the fantastic star display and silently rejoice. Then I tell him a few stories of astronomical trivia. He hadn’t heard about Polaris giving direct measurement of your latitude but of course he knew it was the sailor’s signpost to true north. “Well, not exactly true north. ” I said and then went on to tell him how in human history Polaris has not been so constant. Because of the astronomically slow wobble of earth on its axis every 26,000 years, Polaris has only drifted into a useable true north position during the past 1,500 years or so. Before that the Ancient Greeks noted the north celestial pole was devoid of stars. In another thousand years it will drift away again. Will there still be sailors or desert nomads around to mourn its passing?

Dolphins escort us off the bow.

I show Sergei how to plot our course to clear the shoals extending 30 miles off Cape Fear. Lightning flashes silently inland while above us the skies remain clear. A shooting star drops off the bow and I take to my bunk. All night Sergei diligently trimmed sails and adjusted course to the changing wind. I’m happy to see he is fast becoming a sailor who can captain his own boat. I reflect on his joys of discovery out here and feel them as my own. I envy his ability never to complain or argue, and most of all his ability to fall asleep when off-watch, any time of day or night within a minute of head touching pillow. And I know how well and often he sleeps from the rattling roar of his snoring. Even the snoring has become less irritating as the days go on, like another natural sound of a boat working its way through the sea.

In calm waters, as the wind and seas lay down, I slow myself to match the pace. I capture the mindfulness of here and now. A family of dolphins surround the boat. One in particular eyes me from alongside and slaps his tail against the lightly ripped surface as if to say, “We are here. Don’t you want to join us?” I do notice and am inspired by their free-roaming example.

I get to read two books on this passage, the first I managed to finish in a year of shoreside distractions. Aboard with me were the paperbacks: The Waters in Between, by Kevin Patterson, and the lushly written deep reflections of Passage to Juneau, by Jonathon Raban. Both were excellent shipmates on this trip. Dozens of other worthwhile titles awaited on my e-book reader in case the trip went longer. Still, my need to be productive spills over into sailing as I keep occupied teaching Sergei and scribbling these notes in my journal. No matter that I will pare down much of it during the editing process as unfit to read.

The author at his favorite downwind perch.

Our times of ease and leisure on the flat waters ended the next day when squally weather and headwinds arrived. All the next night we tacked into that obstinate bitch of a southwester, sailing over 45 miles, but making good only 18 miles towards our destination. Get used to life heeled over and pounding while yearning for that forecast wind shift to the NE with the arrival of another cold front. With the rail nearly awash, Sergei clings to the mast monkey-like with one hand while he puts in a second reef. By coincidence, on Sergei’s watch we are on the starboard tack and my bunk is comfortably on the lee side. We tack six hours later and now he has the lee bunk. It worked out well so we kept timing our tacks to the change of watch. All was well when suddenly – Bang! clunk, clunk. In the dark we collided with some floating debris. No real harm done and I was relieved to know I had fit watertight bulkheads forward and aft. We had no exposed prop or strut to damage and the keel hung rudder was safe. She shrugged it off, as she was built to do.

The distant lightning indicating changing weather finally sent us a dark line of clouds that swept away the stars. In the utter darkness there are explosions of light underwater, generated by bioluminescent jellyfish, I imagine. A fair shift in the wind arrives with the clouds when we are some 50 miles off the low shores of South Carolina. We slack the sheets and snug the preventer. A small flying fish bounces off the dodger, hits me in the chest and falls to the cockpit footwell. I toss him back to sea for another chance. If Mei was here, she’d have had him with rice for breakfast.

I had broken Sergei of the habit of waking me for every ship spotted on the horizon. At dawn he announced a ship on a collision course some three miles off the bow. I confirmed it with compass bearings and then the AIS alarm added its confirmation and listed the offending ship by name. When nearly on top of us I grabbed the VHF mic, “Bremen Behemoth, (or some such) this is the sailboat off your port bow. Will you be able to avoid us?” There was a too long silence as I considered tacking away. I imagined the captain thinking, “Little sailboat, if you don’t get out of my way I will crush you to pieces under my bow and then take my breakfast.” Finally the radio crackled with a thick German accent, “OK, I will change course to starboard.” Crisis averted. Another lesson absorbed by Sergei.

The clouds clear away with the fair wind. A brown-backed sea turtle 2-foot in diameter plods by on the surface with head cocked towards me. I wonder if he can summon the energy for a burst of speed to avoid being mauled by some passing ship. Leaping porpoises return to chase flying fish off the bow. All common experiences for a sailor and reason enough to make a short voyage. In the calmer seas and steady winds with only 50 miles to go, Lora is like the horse sighting the barn. The ride is so smooth, as I sit below I imagine the wind has lessened and our speed down to around 3 knots. Again I’m surprised to look up and read 6 knots on the plotter.

It was a pleasure to be on a 44 year old boat for two weeks and discover no leaks above or below the waterline. Despite having over one hundred bolts and screws penetrating the deck and coachroof for all the fittings and hardware, vents, mast wiring, hatches and portlights, not one drop of saltwater entered our refuge even three years after her refit. And nothing breaks. There are few old boats that can say the same after a testing sea passage.

The Norvane steered without complaint aside from the squeaking of her steering lines in their blocks when the sea kicked up as the servo-rudder endlessly swayed from side to side. When apparent wind dropped below four or five knots or the boat speed fell below two knots or when motorsailing, the ST2000 electric tillerpilot took over the helm. The two 50-watt solar panels on tracker mounts and over 400 AH battery bank kept the batteries up regardless of the several days of rain and overcast.

The outboard motor also performed better than I had expected. Its prop never once sucked air in choppy waters as outboards mounted on the transom often do. Is 6HP enough for a 30-foot boat? That depends on your expectations and what type of sailor you are. Over the years I have installed extra-long shaft 6HP motors on four Alberg 30s and I made the owners aware of its limitations. Recently I managed to fit a 9.8HP motor into another Alberg 30 and it has about as much power as a typical inboard engine without the hassles of wasted space, oily bilges, a large metal mass throwing off unwanted heat and noise into the cabin, and the need to either become a diesel mechanic or bring one to your boat from time to time.

Going to sea has always been a reverent event for me. Even a brief passage such as this brings a feeling of escape from the pressures and distractions ashore. To have a crewmate who was without complaint, even when having a touch of seasickness, was a bonus. On this trip I rediscovered I have a reverse seasick response – I am temporarily cured of my too long ashore blues.

As for Sergei’s planned weight loss, we each took in an extra notch in our belts by the time we arrived home. For sure, it ain’t all soft, warm winds and leaping porpoises, but there’s enough of that and more to lure us back again and again.

“Thank you, James,” Sergei said in his heartfelt way after we tied Lora up at her new home slip in Brunswick.

“Sergei, you are now a sailor. My job is done.”

The Alberg 30 Lora back home in Brunswick, GA 2016.

With Sergei’s permission I’ve inserted his comments below:

—————————————————————————–

I enjoyed your excellent article! It reflects the reality of the trip very well.

I am novice in sailing and I had emotions of “green” guy. There were worrying emotions when I was close to let the boat be aground at the entry to river after Norfolk navy base. I had lost ICW marks! But this was one time only.

Thank you, James, for your lessons. There was much to learn and you did this in a most helpful way for me. I’ve not seen more effective practice before. It was good seamanship, trip planning, navigation skills, preparing and maintenance of boat, and even English language improvement.

I watched first time 30-footer can move itself with 6 horse power outboard and 2-reef main together against 15 knots of headwind and steep chopped seas! I did not imagine it earlier.

In spring of last year I asked James:

“Can I repeat your circumnavigation in boats (like Pearson Triton 28, Alberg 30, Cape Dory 30, BAYFIELD 29, Southern Cross 28,31, Bristol 27,30, Westsail 28) along with my wife later when I will ready?”

Then James answered:

“Any of the boats you listed will easily be capable of a circumnavigation for two such as the one I did. The sailors who will say no are sailors who haven’t even tried to do it on these size boats or were lacking in some basic skills and abilities. Of course, you need some time for shakedown passages to get yourself and boat prepared. Boats at least 30′ will be easier for two compared to my Triton 28. A two year circumnavigation is fairly easy to accomplish – three years even easier.”

My trip with you from Branford, CT to Brunswick, GA was my first shakedown passage. With my wife Larissa I feel ready to continue the adventure.

Thank you.

Sergei

————————————————————————–

Hurricane Matthew Update 10 Oct 2016: We arrived back in Brunswick one week before Hurricane Matthew approached. Two days before the hurricane arrived, we moved Atom and Lora from the exposed docks at Frederica Yacht Club to the well-protected Brunswick Landing Marina located six miles inland from the beaches. The eye of the storm passed about 30 miles offshore with hurricane force winds hitting us from NE backing to NW as it passed. I’m happy to report that both boats sustained no damage.

Below is a video of our trip:

Unfortunately, personal issues prevented Sergei from making the longer voyage he had hoped for. Lora was eventually sold to a new owner who has carried on the dream of a world voyage and as of June 2021 was sailing Lora solo from Fiji to Indonesia. Here’s a Youtube video of her continuing saga:

Alberg 30 Lora Begins a Circumnavigation

More details about this boat can be found at: